931 Exhibit

Construction Images

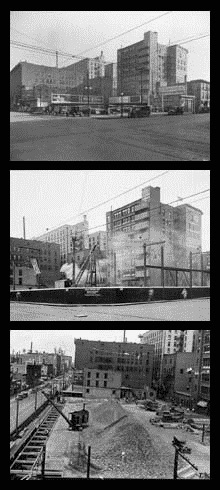

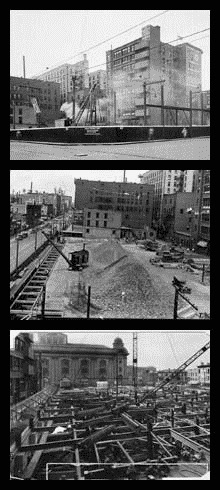

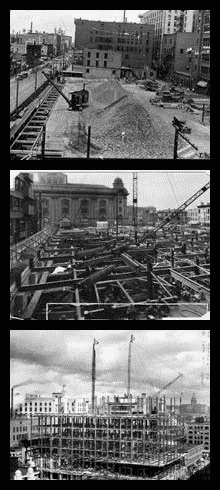

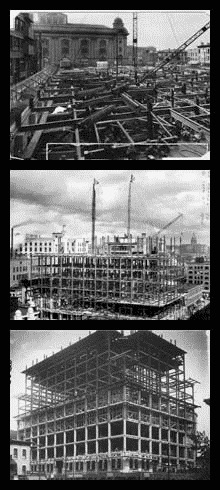

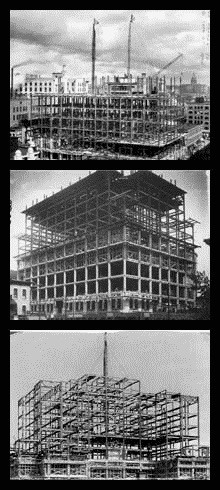

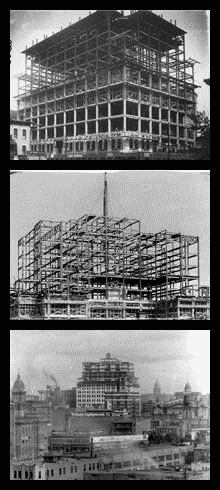

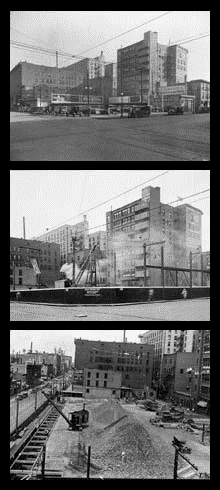

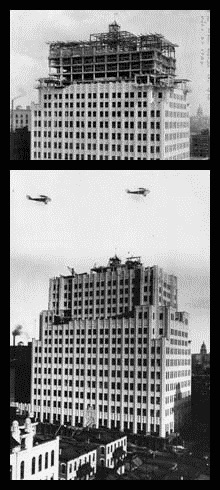

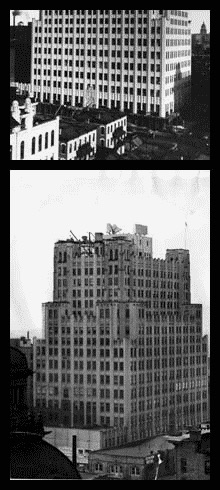

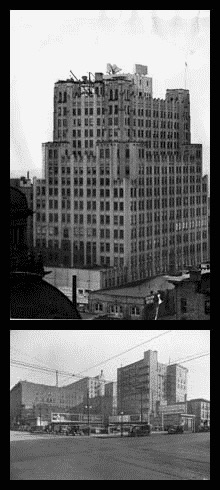

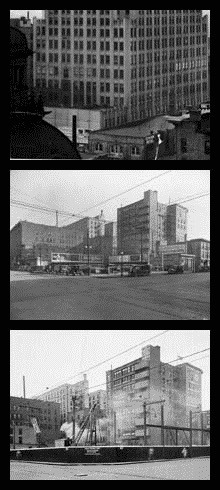

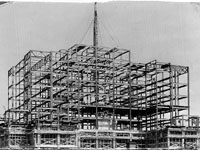

There are many images of the 931 14th St building as it was under construction between 1927 and 1929, since it was an extremely important development in the city of Denver. Below are selections from the THG archives.

931 14th St.

Building Construction

Construction began March 5, 1927, with the demolition of the existing buildings and excavation of a hole 40 feet deep at the site. Work did not even pause when gold–or at least traces of it–were found during the digging. Workers simply panned for gold during their lunch hour.

The builders were the C.E. Walker Construction Company of Denver. They pretty much followed the architectural plans for the building, and it was a massive undertaking. The new building would cover 25,000 square feet of ground. It was set on concrete column footings 8 feet thick, used 4,000 tons of steel and 1,800 tons of terra cotta, included 40 miles of lighting conduit and 80 miles of wire, and contained 1,000 windows and 1,000 doors. And it had to be completed in two years.

The building ended up being 236 feet high; normally, this would have resulted in a 24-story building, but in this case there were only 15 stories. What happened to the missing floors? Higher than usual ceilings were required to accommodate the step switches (which were, of course, one of the primary reasons for building the building). This introduced another issue: six of these switches were required to make a single call, and while each weighed just 22 pounds (roughly as much as a cocker spaniel, Boston terrier, or other small-ish dog), the new building was supposed to accommodate 40,000 simultaneous phone calls—using 240,000 switches, weighing in at a hefty 5,280,000 pounds (2,640 tons, or about 1,200 Ford Explorer SUVs, or 240,000 cocker spaniels), all piled up in relatively little space. The stacks of switches were 11 feet high, requiring a 16′ ceiling to accommodate the cabling and access space necessary above the switches. (Click here

931 Exhibit

Switching Example

How did the switches in the telephone building work? Play the video below to find out!

So what's going on in the video? The caller (left) lifts the handset to establish the circuit, then dials the digits of the telephone number. The dial sends a series of pulses, or clicks, down the circuit to the switch: one pulse for the number "1," three pulses for the number "3," and so on.

The Central Office switch contains banks of 10-level relays, each representing one of the numbers in a telephone number.

Each pulse from the caller's telephone advances a relay bank by one step. In this demonstration, the caller is dialing 341-5555, so the dial sends three pulses, then four pulses, then one pulse, and so on. The combination of connections establishes the path upon which the call goes through, and the called phone rings (right).

Needless to say, the floors had to be made of pretty strong stuff to hold the switches. These floors were made of reinforced concrete and steel, and were made extra thick. Several such reinforced floors were required for the switches. Where possible, local materials were used in construction, partly to follow the Bell System’s architectural ideas and partly because this made it easier to haul the tons of materials necessary to the site.

The granite base used in the street sides of the building came from the Platte Canyon; the walls in the lobbies (Curtis St and 14th St), the business office, and employee entrance were of Colorado travertine; most of the steel structure was rolled in Pueblo mills; and the terra cotta used for facing was manufactured in Denver. Other materials and their locations:

- The 232,000 facing bricks matching the terra cotta, and the 2,000,000 common backing bricks, were produced near Golden by a predecessor of Coors porcelain.

- 67,000 enameled bricks were made in Denver.

- The ornamental wrought iron was fashioned by local artisans, and the installation of heating, plumbing and wiring systems was carried out by Denver firms.

- 22,000 square yards of Jaspa linoleum were installed, the largest ever amount for a single contract.

- The lobby floors are marble—10-inch Swanton Black Vermont marble tiles laid diagonally in combination with Friendsville Dark Pink Tennessee and bordered by strips of Swanton Black.

The finishing touches came by May 1929, and Denver’s “cut-over” to dial service using the step switches took place on May 4, when all of downtown Denver’s phones started using the new service. By July 29 the building was fully occupied and was open for business, and it “officially” opened to the public on August 6, 1929—less than three months before the stock market crashed.

The slideshow above, right: Images from various stages of construction of the 931 building (THG archives). You can click on the slideshow to see the images individually.

(Use the links below to continue exploring this exhibit, or click here to continue a Guided Tour.)

Exhibit Entry | Site History | Local Com History | Architecture | True Murals | Building Tour Drawing Board | Construction | Building in Use

931 14th St.

Building Construction

Construction began March 5, 1927, with the demolition of the existing buildings and excavation of a hole 40 feet deep at the site. Work did not even pause when gold–or at least traces of it–were found during the digging. Workers simply panned for gold during their lunch hour.

The builders were the C.E. Walker Construction Company of Denver. They pretty much followed the architectural plans for the building, and it was a massive undertaking. The new building would cover 25,000 square feet of ground. It was set on concrete column footings 8 feet thick, used 4,000 tons of steel and 1,800 tons of terra cotta, included 40 miles of lighting conduit and 80 miles of wire, and contained 1,000 windows and 1,000 doors. And it had to be completed in two years.

The building ended up being 236 feet high; normally, this would have resulted in a 24-story building, but in this case there were only 15 stories. What happened to the missing floors? Higher than usual ceilings were required to accommodate the step switches (which were, of course, one of the primary reasons for building the building). This introduced another issue: six of these switches were required to make a single call, and while each weighed just 22 pounds (roughly as much as a cocker spaniel, Boston terrier, or other small-ish dog), the new building was supposed to accommodate 40,000 simultaneous phone calls—using 240,000 switches, weighing in at a hefty 5,280,000 pounds (2,640 tons, or about 1,200 Ford Explorer SUVs, or 240,000 cocker spaniels), all piled up in relatively little space. The stacks of switches were 11 feet high, requiring a 16′ ceiling to accommodate the cabling and access space necessary above the switches. (Click here

931 Exhibit

Switching Example

How did the switches in the telephone building work? Play the video below to find out!

So what's going on in the video? The caller (left) lifts the handset to establish the circuit, then dials the digits of the telephone number. The dial sends a series of pulses, or clicks, down the circuit to the switch: one pulse for the number "1," three pulses for the number "3," and so on.

The Central Office switch contains banks of 10-level relays, each representing one of the numbers in a telephone number.

Each pulse from the caller's telephone advances a relay bank by one step. In this demonstration, the caller is dialing 341-5555, so the dial sends three pulses, then four pulses, then one pulse, and so on. The combination of connections establishes the path upon which the call goes through, and the called phone rings (right).

Needless to say, the floors had to be made of pretty strong stuff to hold the switches. These floors were made of reinforced concrete and steel, and were made extra thick. Several such reinforced floors were required for the switches. Where possible, local materials were used in construction, partly to follow the Bell System’s architectural ideas and partly because this made it easier to haul the tons of materials necessary to the site.

The granite base used in the street sides of the building came from the Platte Canyon; the walls in the lobbies (Curtis St and 14th St), the business office, and employee entrance were of Colorado travertine; most of the steel structure was rolled in Pueblo mills; and the terra cotta used for facing was manufactured in Denver. Other materials and their locations:

- The 232,000 facing bricks matching the terra cotta, and the 2,000,000 common backing bricks, were produced near Golden by a predecessor of Coors porcelain.

- 67,000 enameled bricks were made in Denver.

- The ornamental wrought iron was fashioned by local artisans, and the installation of heating, plumbing and wiring systems was carried out by Denver firms.

- 22,000 square yards of Jaspa linoleum were installed, the largest ever amount for a single contract.

- The lobby floors are marble—10-inch Swanton Black Vermont marble tiles laid diagonally in combination with Friendsville Dark Pink Tennessee and bordered by strips of Swanton Black.

The finishing touches came by May 1929, and Denver’s “cut-over” to dial service using the step switches took place on May 4, when all of downtown Denver’s phones started using the new service. By July 29 the building was fully occupied and was open for business, and it “officially” opened to the public on August 6, 1929—less than three months before the stock market crashed.

The slideshow above, right: Images from various stages of construction of the 931 building. (THG archives).

(Use the links below to continue exploring this exhibit, or click here to continue a Guided Tour.)

back to top

back to Drawing Board

on to Building In Use

Exhibit Entry | Site History | Local Com History | Architecture | True Murals | Building Tour

Drawing Board | Construction | Building in Use